karl_kaboom

TPF Noob!

- Joined

- Mar 13, 2014

- Messages

- 3

- Reaction score

- 0

- Location

- Ohio

- Can others edit my Photos

- Photos OK to edit

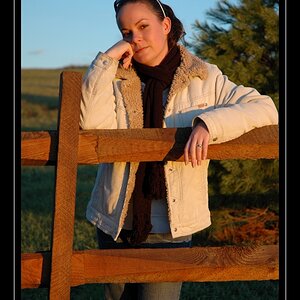

Complete novice requesting advice from a pro. I'm going to be tasked with photographing a very large number of antique advertising items. They consist primarily of 3 subject types: Lithographed tin serving trays approximately 12-14" in diameter (as per below example), large flat tin advertising signs approximately 36-48" in either dimension, and paper lithographs framed behind glass approximately 36-48" in either dimension.

Camera: Canon SX40HS.

Conditions: Interior only, under controlled lighting, with tripod.

My question is concerning the elimination of glare from the light sources, which in my case, is two 105 watt lights (marked "105W 5500K 110V 60Hz") inside two 19x19" soft boxes on stands.

Taking advice from online sources, I did the following: Put two 19x19 polarizing sheets in front of my two light sources, set them at 45° to the subject, and used a circular polarizer on the camera lens. These are the specs of the polarizing sheets I used: "Transmittance: single(43%); parallel(38.1%); crossed(0.056%). Color: neutral gray. Polarizing efficiency: 99.9%".

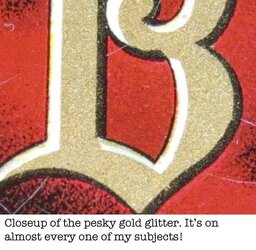

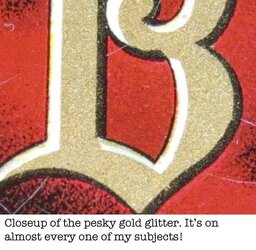

As expected, the sheets and lens filter did eliminate all glare, but created a new problem. I immediately realized that virtually every subject that I need to photograph features a speckled, vibrant, almost glittery gold color that was apparently quite popular in circa 1900 advertising items. The polarizers seem to kill this vibrant gold color right along with the glare.

To see the affect that the polarizers are having on this vibrant gold color, see my two examples below -- one taken without the polarizers (and, hence, with two glare spots), and one taken with the polarizers. Look, in particular, at the phrase "Beer, Ale and Porter" in the lower right corner of the tray. The polarizers have almost completely blotted out the vibrant gold tone.

Can someone please educate me as to how I can fix this problem, i.e. specifically, 1) eliminate glare, but 2) do not blot out any of the other vibrant colors in the subject.

FYI: Setting the camera at an angle to the subject in order to eliminate glare is not an option in my case. These will need to be 90° straight-on shots.

Thanks in advance for your help! Please, no guesswork. I'm tapped out on time and resources. I need experienced insight. Thanks!

Camera: Canon SX40HS.

Conditions: Interior only, under controlled lighting, with tripod.

My question is concerning the elimination of glare from the light sources, which in my case, is two 105 watt lights (marked "105W 5500K 110V 60Hz") inside two 19x19" soft boxes on stands.

Taking advice from online sources, I did the following: Put two 19x19 polarizing sheets in front of my two light sources, set them at 45° to the subject, and used a circular polarizer on the camera lens. These are the specs of the polarizing sheets I used: "Transmittance: single(43%); parallel(38.1%); crossed(0.056%). Color: neutral gray. Polarizing efficiency: 99.9%".

As expected, the sheets and lens filter did eliminate all glare, but created a new problem. I immediately realized that virtually every subject that I need to photograph features a speckled, vibrant, almost glittery gold color that was apparently quite popular in circa 1900 advertising items. The polarizers seem to kill this vibrant gold color right along with the glare.

To see the affect that the polarizers are having on this vibrant gold color, see my two examples below -- one taken without the polarizers (and, hence, with two glare spots), and one taken with the polarizers. Look, in particular, at the phrase "Beer, Ale and Porter" in the lower right corner of the tray. The polarizers have almost completely blotted out the vibrant gold tone.

Can someone please educate me as to how I can fix this problem, i.e. specifically, 1) eliminate glare, but 2) do not blot out any of the other vibrant colors in the subject.

FYI: Setting the camera at an angle to the subject in order to eliminate glare is not an option in my case. These will need to be 90° straight-on shots.

Thanks in advance for your help! Please, no guesswork. I'm tapped out on time and resources. I need experienced insight. Thanks!

![[No title]](/data/xfmg/thumbnail/32/32164-d68fa2de02f9bef524bbd68aac2f12e4.jpg?1619735234)