AlanKlein

Been spending a lot of time on here!

- Joined

- Nov 24, 2011

- Messages

- 2,265

- Reaction score

- 816

- Location

- NJ formerly NYC

- Website

- www.flickr.com

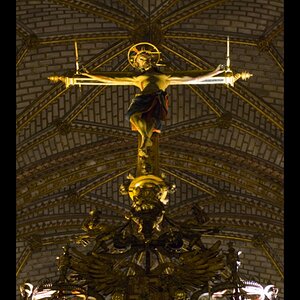

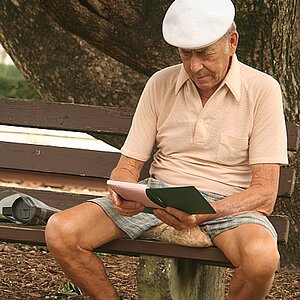

The compositional point of shooting however is EMPHASIS on the subject and there is NO emphasis on the subject in a perfectly balanced image.

The perfectly balanced picture is when you place the subject in the middle if there are no other elements, like a portraiture. Howewver, by placing the main subject in the middle when there are other elements in the shot, is that the other elements draw the eye away from the main subject into either the negative area or other area where other objects are located. By balancing the elements, you remove that effect. Plus the eye isn't fixed. It moves around through the whole picture. Then the brain assembles the photo into something that is not what the eye is seeing. Maybe balance sets off aesthetic enzymes or whatever in the brain. So in a way, a balanced picture where the subject is off center, creates a better emphasis on the main subject even though it's off center as long as other elements balance the composition.

I'm sorry, but after reading the above several times, it is as clear as mud. If the subject is off centre in accordance with the rule of thirds, then it is not a perfectly balanced image.

I never mentioned rule-of-thirds. I was talking about balance. I said that if the main subject is on one side, it should be balanced against something on the other side. Re-read the last sentence in my last post.

![[No title]](/data/xfmg/thumbnail/41/41759-f0f73c457ebcb6dabcbddc7a3c000487.jpg?1619739884)

![[No title]](/data/xfmg/thumbnail/41/41762-58f644e561db7433f4f566037a965217.jpg?1619739884)

![[No title]](/data/xfmg/thumbnail/41/41760-e5b9dc90c1289f677ce3ca9dc1fa6dde.jpg?1619739884)