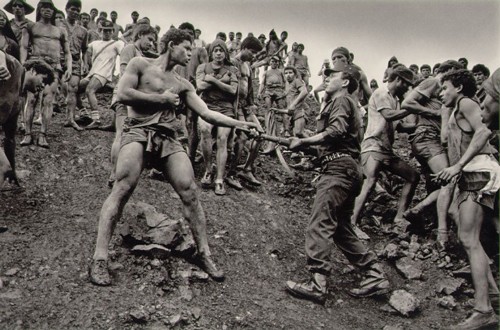

What difference does it make? A lot! There is actually some compositional merit in the one shot....

http://www.photographyboard.net/rugby-game-1087.html

Study it carefully. Note the lower left to upper right diagonal 'movement'.

You've missed the point here, it really doesn't make any difference, we are talking about two different things.

What I was saying is... to the viewer it doesn't make any difference what the technical settings where when capturing an image. Photography is (or should be) much more harsh than that.... it is visual and therefore people make up their minds if they like (or connect with) the shot within a few seconds.

How it is captured is largely irrelevant.

No, I don't appreciate 'landscape photography'. It's banal and appeals to bourgeois tastes. It is a remnant of Romanticism, which I repudiate. You probably have no idea what I'm talking about. Oh well...

I know exactly what you are talking about, but in my opinion and the opinion of millions of others you are wrong. Landscape, certainly today, is not all about Romanticism, it is way beyond that.

Again this goes back to my point of what

you see in photographs... what

you look for and your own associations made to the elements of the scene.

For example, I look for light placement, colours + textures (in a purely aesthetic sense), and most importantly awe inspiring views of the natural earth. Sure, landscapes can convey the sense of nostalgia and/or fantasy which could be considered Romanticism, but to dismiss this style of photography as just that is really missing the point.

You misread the quote. Someone in Culture Club said if he went to someone's house and saw an Eric Clapton record he would leave. When people start blathering on about landscape work or Ansel Adams to me, I leave...

I dont know whats worse... the way I read it, or the fact that someone from Culture Club is knocking Eric Clapton

You may find this interesting (not saying I agree or disagree, just showing some other points of view):

Ansel Adams: But is it art?

"Throughout the affluent world, and above all in the United States, Adams's wilderness studies are the staple of the gift store rather than the cutting-edge art gallery, and for every person who has ever seen an Adams print at close range there will be umpteen who know his work only from coffee-table books, glossy calendars, postcards and other studiedly tasteful bric-a-brac.

More than any other photographer, Adams has become established as the one you can take home to show the folks, with perfect confidence that he will ruffle no feathers, spoil no one's supper, so that the mass reproduction of images he made – mostly before 1949 – has grown into the kind of booming industry usually felt to be incompatible with photographic talents of the first rank."

"The escalating value of a Moonrise print is also a handy index of the sudden boom in the photographic collectors' market from the late 1970s onwards. In the late 1940s, Adams would sell a 16-by-20 print for just $50 (£32); in December 1979, an auction at Sotheby's in New York set three sales records when it brought in a successful bid of $22,000 (£14,000) for one of the same prints – the most ever paid up to that point for a work by a living photographer, the most ever paid for a 20th-century photograph, and the most for a work on paper. Since then, the Moonrise edition has gone on to make a vast sum in the resale market – a modest estimate being more than $25m (£16m).

All of which might point to little more than herd instinct and chronic poor taste among rich collectors, and a fortune made on the back of unfashionable inoffensiveness. There is something in this: considered cynically, Adams's photographs of the American West are spiritual cousins to those Impressionist studies of rural France so beloved of Japanese financiers. You don't need a higher degree in fine art to find them easy on the eye."

"The f/64 group was an avant-garde and, like all avant-gardes, its members were destined to be rejected by their juniors. Serious complaints about Adams's work became audible after the Second World War, and grew louder with the 1950s and 1960s, when the likes of Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand and William Klein came to the forefront of critical attention. Their work was variously rough-edged, jaundiced, improvised, harsh, neurotic, obsessive and unsettling: the polar opposite of everything Adams had accomplished, and, to the post-war sensibility, an exhilarating novelty. The task of photography, critics now tended to say, was more to shock and dismay than to celebrate and sooth, and if the ideal of "beauty" was to be evoked at all, it was more a question of discovering a fascination in the discarded or grotesque than in traditional canons of wholeness, harmony and radiance. It's a fair cop, as far as it goes. Klein, Frank and company are still very much critically OK, and will no doubt remain so as long as there is no such thing as a Diane Arbus wall calendar or desk diary, with freak-of-the-month displays. But there is, too, such a thing as the philistinism of the elite: a refusal to see the virtue of something popular simply because it is popular, or to take pleasure in a conventionally beautiful image simply because, like an Adams photograph, its beauty is conventional, "unchallenging", merely pretty.

At the very least, Adams deserves the tribute of open-mindedness and informed criticism; and one anecdote that should always be a small part of the whole story is that which tells how the critic Beaumont Newhall, idly flicking through a magazine, unexpectedly came across an Ansel Adams picture which made him literally fall back on the couch in surprise, murmuring that Adams must surely be the greatest photographer ever."

![[No title]](/data/xfmg/thumbnail/42/42269-bc38cb35884d46241dcf3623b338b43b.jpg?1734176665)

![[No title]](/data/xfmg/thumbnail/32/32630-d78de94d84be2acf57d5e0923482b4da.jpg?1734162115)